Wright City, Oklahoma, may be a small town, but it’s got a great big heart. Perhaps no one knows that better than hometown girl Claire Green Young. In a town like Wright City, everyone knows their neighbors, and a helping hand is never far away.

“Everyone kind of takes care of each other, and there’s a lot of positive spirit surrounding that kind of communal aspect of how everyone gets along,” said Claire. “If you’re not at a basketball game on a Friday night, you might be at a church event or at a community bake sale. You’re seeing everyone. You’re at the community center playing bingo.”

Claire’s roots in the area go back multiple generations. She actually grew up in a tiny community just outside Wright City called Herndon, named for some of her ancestors. One of the Herndon brothers married the Choctaw matriarch of Claire’s family.

“My grandfather attended Herndon school while it was still open, and today, my grandparents live on the same property where the old school building used to be. It’s special to have that connection,” said Claire.

At home, Claire’s mother, Ellen Green Young, was the rock she and her brother needed. Being a single mother with a full-time job as a dietician didn’t stop Ellen from being there to support her children as they grew up. Young Claire looked up to her mother for her strength and determination. She still looks up to her today for those same reasons.

“She’s just one of the most incredible women I’ve ever met,” said Claire.

Serving the community in a meaningful way is a value Ellen keeps and has passed on to her children. As executive director of the nonprofit Feed the Need Foundation for Rural Oklahoma, she has built a program that ensures the nutritional needs of elders are met.

“I feel really blessed to have had that experience and exposure to the kind of incredible work and the kind of embodiment of servant leadership that she upholds in our community,” said Claire of her mother’s efforts.

Seeing how hard her mother worked to give back to others and be successful was Claire’s greatest inspiration to step out of her comfort zone when an opportunity to visit an ivy league college came her way.

"I feel really blessed to have had that experience and exposure to the kind of incredible work and the kind of embodiment of servant leadership that she upholds in our community," said Claire of her mother's efforts.

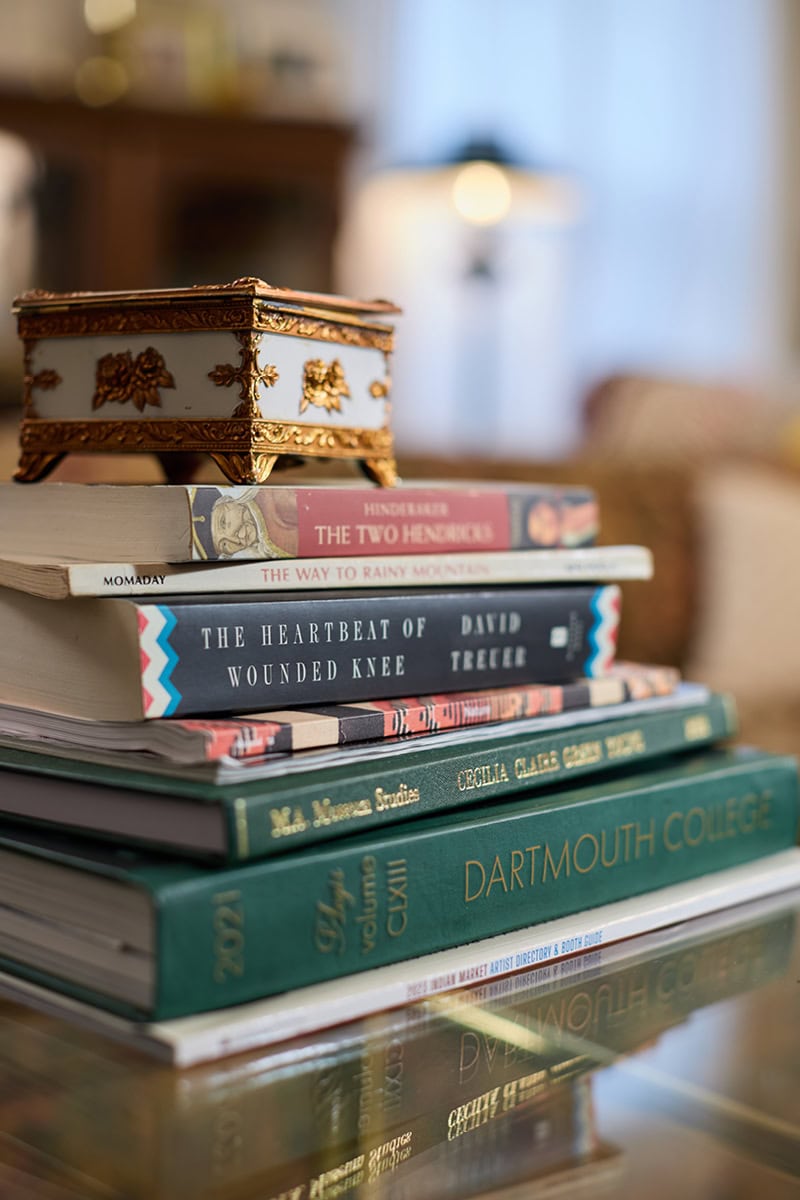

Dartmouth College’s Indigenous Fly-In program is designed for Native American high school seniors who want to see what an ivy league experience would be like for them. Claire didn’t expect to be accepted to the program, but she knew she would regret it if she didn’t at least try.

But her risk paid off.

By the end of her first day, Claire had decided Dartmouth was where she needed to be, and she applied for early decision admission, an intensive process requiring lots of time, commitment, and hard work. Of course, it meant taking another chance on something that may not work out. Dartmouth is all the way in New Hampshire, farther away than she had ever been from home and for a longer amount of time. Not to mention the tuition costs at Dartmouth are pretty steep.

Not only was Claire accepted on early decision, but she also earned a generous financial aid package in addition to various scholarships from the Chahta Foundation and Choctaw Nation Higher Education. Her dream was actually coming true!

“I felt really driven to push myself in this way. And when I got that acceptance letter, it was almost a bittersweet moment for me. It took a while to tell people just because I do love that town and those people a lot,” said Claire. “It took some time to get used to the idea of leaving and growing up.”

For Claire, Dartmouth was just the first step in seeing the world, however. She studied abroad in London and Edinburgh, which fueled her passion for visiting other countries and cultures. Today, she has been to 21 different countries.

Upon her graduation from Dartmouth, Claire got the news that she had been selected as the Choctaw-Ireland Scholarship recipient. Honoring the friendship between the Choctaw and Irish people forged during the potato famine in 1847, the program gives Choctaw college students the opportunity to study in Ireland. A chance encounter there with an Irish local became one of many that helped Claire see that her place was back home with her tribe.

After a television interview at an old famine village site, Claire returned to her hotel in her full Choctaw regalia. An Irish man approached her in the lobby and asked about her dress. When she told him she was Choctaw and explained the symbolism of the regalia, he knew exactly who she was.

“Can I just give you a hug from my ancestors to yours to say thank you for all you’ve done?” asked the stranger.

“And that was one of the most powerful moments that I had,” said Claire. “It was a really beautiful time and a really reassuring moment for me to hear from a complete stranger that his connection was something that meant so much to him, and it made me feel like this was a right time, right place kind of thing.”

"It was a really beautiful time and a really reassuring moment for me to hear from a complete stranger that his connection was something that meant so much to him, and it made me feel like this was a right time, right place kind of thing."

Small moments and revelations along her journey seemed to point her towards Chahta art and culture. A stint as the Mellon Foundation Curatorial Fellow of Native American Art at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma was her first experience working in a museum. Much like her Fly-In experience at Dartmouth, it gave her a feeling of instant connection with her destiny.

“I was just blown away by the back of house, you know, going into collections and seeing these massive, incredible pieces of art hanging and gorgeous pottery. I wanted to be part of that,” said Claire. “I felt like it was a moment where I also knew these are things I care about. Not just the art side of things, but the community side of things.”

Upon her return to the Choctaw Nation, Claire accepted the position of Curator at the Choctaw Cultural Center. Her first curated exhibit, Bok Abaiya: Practiced Hands and the Arts of Choctaw Basketry, on display through March 30, 2024, centers on generations of Chahta basket weavers and the ways they have used natural resources to craft functional, yet beautiful, vessels.

“I hope that…you can tell that this isn’t just an exhibit about baskets; this is an exhibit about Choctaw people,” Claire said.

In February, Claire began a position with the Choctaw Nation’s Communications Division as the Public Arts Manager, where she will continue to support Chahta artists and share their work with communities across the reservation.

And she is happy to be back home.

“I think it speaks to the fact that being from this small place doesn’t mean that you have to stay forever. It doesn’t mean you have to leave forever,” said Claire. “I think that if I hadn’t left and gone out and experienced the world the way that I did, I don’t think that I would have been as motivated to recognize the extent to which I was so grounded in the place, in the people here.”